The past couple of years I’ve been obsessing over the English folktale ‘George and The Dragon’.

There is a lot to work with in this story, from the potential to interpret the elements as alchemical elements as proposed by Estelle Alma Maré or Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene in which George acts as liberator for a terrorised village. The Dragon and George exist as opposites representing both the hero-villain good/evil dynamic and the physical/psychological aspects of humankind.

The ‘Golden Legend’ (Jacopo de Voragine, 1292) is the first time that the George and the Dragon story caught on, the original tale in all its gory glory sees a pagan princess (of Silena) terrorised by a dragon, a saint who captures and the dragon and parades it as a trophy. Promptly followed by the classic mediaeval coercion into forced adoption of Christianity for the pagan villagers, at which point George finally kills the enslaved dragon. It makes for some pretty dark reading.

Many of you who are familiar with the UK will have seen small children celebrating Saint George on 23 April each year generally with flag making, sword play and papier mache dragons. The sanitised version of the folklore that I was most familiar with prior to this project talks about a dragon wreaking havoc, a king trying to appease the dragon by offering his daughter as sacrifice (admittedly still dark stuff) and a hero riding in to save the day.

The story of George and the dragon is viewed as a parable of the triumph of good over evil, and it has become a popular subject for art, literature, and film.

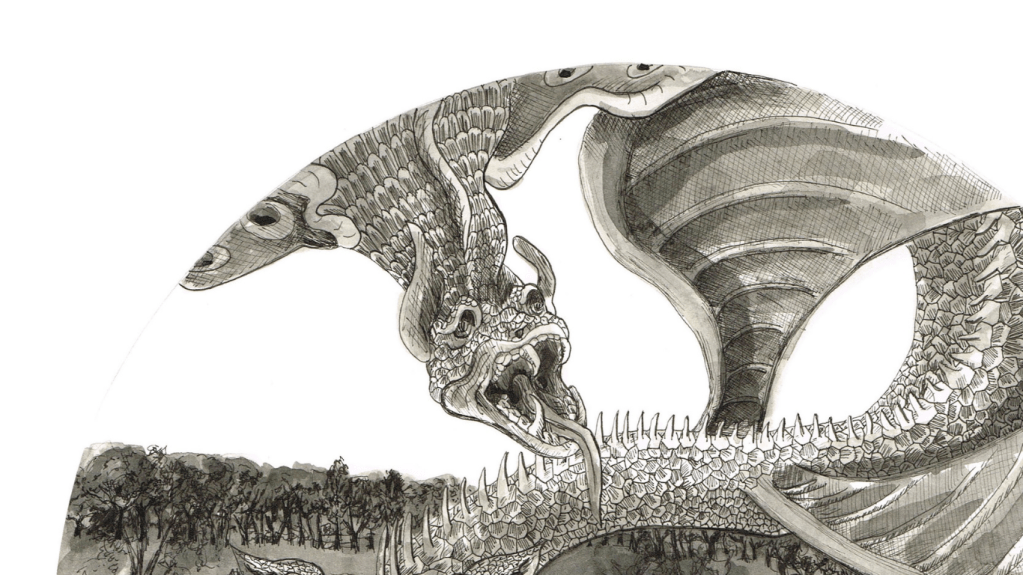

From the art side, the National Gallery hosts the Uccello painting of Saint George and the Dragon, perhaps more famous for it’s stunning use of perspective than the subject matter itself. I’ve referenced Uccello’s dragon multiple times as I love way Uccello has conveyed a bloodthirsty devilish monster contrasted with a passive, resigned princess. That juxtaposition of action and inaction saying so much about the roles that characters are cast into.

Just how did such a gory and frankly horrible story because the stuff of school plays? Moreover, how did a Roman Army Officer end up as patron saint of England? historic-uk.com gives a very readable answer to this later question, even expanding into who the original (English) Saint of England was.

It’s hard to look into the art of the legend without referencing the romantic movement. As an artist living near Birmingham UK I’ve of course got to get a reference to the Pre-Raphaelites in too – with this Watercolour & Bodycolour over Ink from Rossetti as a classic of the chivalry celebrating genre.

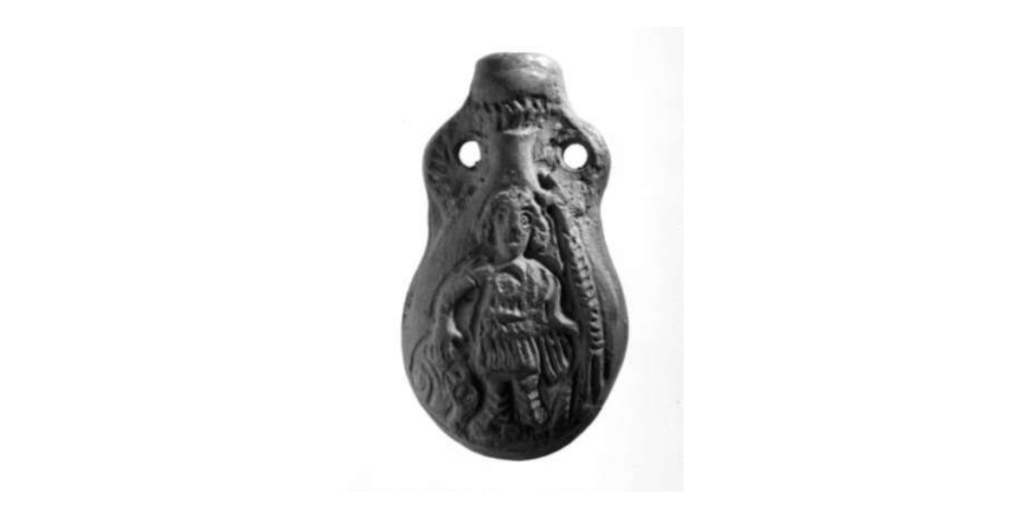

The figure of the dragon is widely considered to be a later addition to the Saint George tale and to represent the devil and forces of evil, rather than a literal dragon. Prior to the ‘Golden Legend’ there are other paintings of dragon fights so the motif of a warrior knight defeating a devil dragon seems to have been rooted in the imagination prior to the thirteenth century. Indeed, the British Museum has a beautiful example of a saint and dragon serpent pilgrim flask from the Early Byzantine period (fifth-sixth century).

Perhaps this quick run through of the legend will inspire you also, there are so many facets to the tale to explore!

REFERENCE LINKS

The Golden Legend | Glossary | National Gallery, London

Paolo Uccello | Saint George and the Dragon | NG6294 | National Gallery, London

St George – Patron Saint of England (historic-uk.com)

9 things you didn’t know about St George | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk)

Leave a comment